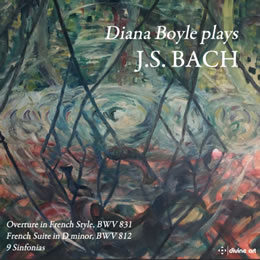

Diana Boyle breathes fresh life into Mozart’s piano sonatas on a new release from Divine Art

Pianist Diana Boyle www.dianaboyle.com was born in London and educated at St Paul’s Girls' School and as a Foundation Scholar at the Royal College of Music. In 1970 she continued her studies under Enrique Barenboim in Tel Aviv and, in 1973, was awarded a Fulbright Scholarship to study with Artur Balsam in New York.

After making her London recital debut in 1979 she gave concerts in the USA, Canada, Spain, Portugal and England. She also taught piano and chamber music in London and in the USA. In 1987, Diana Boyle was invited to make a series of recordings for National Public Radio in Boston, including performances of the Bach Partitas. In 1990 Diana Boyle returned to the Bach Partitas, recording this time at Forde Abbey in Dorset, England for Integra Records.

Since then Diana Boyle has recorded Bach’s Well Tempered Clavier Book 2 for Metier (MSVCD 2002) and Bach’s Art of Fugue for Divine Art (dda 25097).

Now from Divine Art Recordings www.divine-art.co.uk/DAhome.htm comes a 2 CD release of piano sonatas by Mozart.

Diana Boyle opens Disc 1 with Mozart’s Piano Sonata in C major, K.279 providing a lovely clarity to the Allegro, assisted enormously by the wonderfully clear and detailed recording. She brings the feeling of discovery, new delights at every turn, wonderfully phrased, finding new ways to explore this music. There is a quite exquisite, thoughtful Andante, intimate in its gentle delicate beauty and a wonderfully, finely pointed, rhythmic Allegro, again beautifully shaped and often with a rather nonchalant spring to her playing, finding many little details.

The Allegro of the Piano Sonata in G major, K.283 brings a wonderfully intimate performance with a lovely flow, finely phrased with some exquisite little details where every note is finely shaped. The Andante slowly reveals Mozart’s well constructed phrases with a beautifully judged tempo, finding every nuance. There is a terrific rhythmic spring to the Presto yet observing every little variation of tempo and dynamic. There are passages of fine Mozartian forward drive but always with terrific clarity before a wonderful conclusion to this sonata.

Diana Boyle brings a jewel like, delicate purity to the Allegro moderato of the Piano Sonata in C major, K.330. Such clarity allows every little turn and harmonic shift to be clearly heard. There is a gloriously drawn Andante cantabile with this pianist finding a subtly poignant emotion as she very slowly reveals Mozart’s lovely creation. Finally there is a nice, crisp Allegretto with some finely done left hand phrases, wonderfully fluent yet with a clear and crisp rhythm.

Boyle brings some fine dramatic phrases to launch the Molto allegro of the Piano Sonata in C minor, K.457, her clarity and purity still adding so much, a lovely delicate fluency with some richer textures at times. The Adagio of this sonata is probably the slowest and most idiosyncratic of all, often stretching Mozart’s ideas to the extreme, yet revealing so much in its beautifully shaped form, almost as though the composer is sitting at the piano trying out ideas. It certainly builds a mesmerising intensity. The Allegro assai picks up a fine tempo with some wonderfully fluent phrases, rolling forward through passages that are finely shaped and phrased with a rubato, before finding some moments of quiet repose before the coda.

Disc: 2 opens with the Piano Sonata in B flat major, K.281 and an Allegro that brings a forward rolling fluency before picking up Mozart’s lovely rhythmic theme. There is such exquisite care of dynamics and phrasing and again that pin point clarity. This pianist brings an nicely shaped opening to the Andante amoroso, Boyle finding every little detail with terrific phrasing and dynamics, soon finding a gentle flow with subtle little variations of rhythm and tempo. The Rondeau: Allegro has a lovely tempo, never rushed, allowing Mozart’s every detail to emerge.

Diana Boyle carefully develops the Adagio of the Piano Sonata in E flat major, K.282, slowly gaining in tempo to achieve a wonderfully crystalline flow. Menuetto I has a lovely rhythmic skip, Boyle’s light touch bringing a rather special quality, clear and crisp. Menuetto II achieves more of a flow yet still with some quite lovely rhythmic variations. The Allegro has a good forward moving flow with some fine harmonies revealed by this pianist.

The Rondo, K.494 was first performed alone in 1786, whereas the Allegro and Andante, K.533 followed in 1788. Mozart joined the pieces with an expanded K.494 to form the Piano Sonata in F major. The Allegro (K.533) has a faltering rising and falling flow, this pianist finding some lovely phrases with passages of increased dynamic contrast. The Andante (K.533) slowly reveals passages of fine beauty as this pianist slowly develops this exquisite movement with some most lovely phrases as she teases out many lovely Mozartian ideas. She concluded with a crisp, rhythmically pointed Rondeau: Allegretto (K.494) bringing a wonderful clarity with a lovely subtle, delicate flow, revealing this to be a real jewel.

The Allegro of the Piano Sonata in B flat major, K.570 has a lovely slow introduction before finding a rhythmic poise with this pianist’s phrasing, use of dynamics and varied tempi revealing so any lovely facets. She brings gravity to the Adagio, each note carefully considered with moments of light and gentle rhythmic bounce, quite exquisitely done. She brings her really fine crisp and buoyant playing to the Allegretto with some lovely left hand phrases.

Diana Boyle breathes fresh life into these sonatas. It is true that occasionally her approach is rather idiosyncratic but always supremely musical. Those who expect their Mozart to be more muscular will want to look elsewhere but for me this is not what these sonatas are about. These fine performances take a welcome place on my shelves.

She receives an excellent recording full of detail and presence, with her piano tone perfectly caught. There are notes in the form of an interview with the pianist.

Bruce Reader (The Classical Reviewer)

Bruce Reader (The Classical Reviewer)

May 2016

The Sunday Times <Culture>

The Sunday Times <Culture> WBUR FM, Boston

WBUR FM, Boston